WORDS: NIKOLA POPOVIĆ

PHOTOS: KARIM SAKR

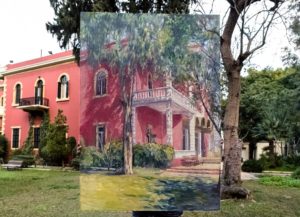

Currently living and working in Beirut, Tom Young (1973) is an artist whose topics refer to past and remembrance, and the city as a litmus paper of history. His techniques include thick impasto oil and thin watercolour washes. An architect by training, a painter by vocation, Tom has had exhibits all over the world. While still waiting for his visit to the Balkans, I am thanking again my friend for his “Rose House” painting, used for my book “Stories from Lebanon”. And here we are, talking over Skype as that day on the terrace of the Rose House, about his life journey from London to Beirut, his past and current projects, Beirut as inspiration for his work…

1) SINCE ANCIENT TIMES, BEIRUT, AND THE MIDDLE EAST IN GENERAL, HAVE ATTRACTED TRAVELLERS FROM THE WEST. THE CITY OF BEIRUT, IN THE TIMES OF THE EMIR FAKHREDDINE WHO TRAVELLED TO ITALY AND DREAMED OF BRINGING THE RENAISSANCE TO HIS LEVANTINE HOMELAND, HAS BEEN A HARBOUR FOR ALL THOSE WHO ARE PERSECUTED AS IS THE CASE TODAY WITH SYRIAN REFUGEES AND MANY TRAVELLERS HAVE LEFT THEIR ANCHOR HERE… WHY BEIRUT?

Beirut attracted me for many reasons –like so many Western travellers before me, I’m drawn to the beautiful weather, light, food, wine, music, culture, mountains, sea, extraordinary mix of civilisations and cultural influences… the people are also generous and welcoming – certainly to me. And also, the extraordinary paradox of the place fascinates me. How can a place be such a paradise, and such a nightmare at the same time? On a deep level, it sets off many emotional triggers in me. I experienced tragedy as a child: my mother died in traumatic circumstances when I was 10 years old, and a seemingly idyllic childhood suddenly changed. But my family has had difficulty dealing with her death ever since. I felt something deeply familiar about Lebanon. This goes beyond nationality – the fact I’m British in a foreign land is not the point. There is emotional resonance. Learning about Beirut’s ‘Golden Age’ in the 60’s and early 70’s, which was abruptly interrupted by the devastating 15- year Civil War, how these memories have been wiped away or lost, whilst the trauma of the Civil War is also glossed over, and not really dealt with because it is too difficult to face. These issues strike chords with me. You can see it in the pockmarked older buildings you see in the city today, the way that old mansions are left abandoned and often demolished to make way for gleaming new towers. The architecture of the city is its barometer of emotion. I have never seen a place like this. For an artist, its an amazing theatre to paint.

And of course, as you suggest, many people don’t come to Lebanon by choice. In the past 100 years, there have been three massive waves of immigration by refugees from Armenia in 1915, Palestine in 1948 and 1967 and now Syria (2011 – )- all escaping danger and conflict in their own lands. The sheer numbers of refugees compared the the local population make the ‘Migrant Crisis’ in Europe at the moment look small in comparison. The conditions the refugees live in, and the place each community finds in Lebanese society vary wildly from affluence and acceptance, to rejection and poverty. Most Palestinians and Syrians live in dreadful conditions. To some extent though, Lebanon is a fairly safe harbour for those escaping conflict in the region. I talked with the Armenian Patriarch and he told me how those Armenians fleeing the Genocide came to Lebanon because it was the only place in the region with a large and politically strong Christian population.

2) HOW MUCH HAS LIVING IN THE MIDDLE EAST SHAPED YOU AS AN ARTIST? WHAT DOES THIS ENVIRONMENT GIVE IN THE SENSE OF SHAPES, COLOURS AND PERSPECTIVE, AND WHAT DOES IT ADD TO YOUR POETICS?

Living in Lebanon woke me up – as a person and as an artist. The two are inextricably linked. Its impossible not to be affected by the chaotic energy of Beirut. It shakes me out of my comfort zone. Before coming to Lebanon, I had got into a rut in London. My work was based around making traditional landscapes to order, and just making enough money to survive, but I knew I had so much more inside. I was capable of much more. But I didn’t know how or what until I came to Beirut. I found a challenging new context for my work, and ways to transform the pain and joy I feel (and see around me) into something meaningful.

I began to use paint in a different way – painting something carefully and then wiping it – to obscure the image and suggest a feeling of movement and something disappearing or being hidden. I also used more white in the paint to suggest the blinding light which reflects off the sea, and the sense of blurred vision. More recently I have built up thick textures of abstract oil paint and then only partially painted the final image on top of these layers to suggest a feeling of archaeology- as if hidden lives and stories are under the surface. For my most recent project, I was working a lot with children from Dar Al Aytam Islamic orphanage, and their energy and youthful spirit inspired me to use brighter colours and a more spontaneous gestural approach to painting.

The city itself is rich in subject matter – apart from the contrasts of new and old, rich and poor, I have begun to use symbolic narrative motifs like Carousels and Ferris Wheels spinning in rubbish dumps and refugee camps to suggest a sense of glowing light, joy and celebration, resilience in the face of adversity and at the same time a kind of damaging escapist amnesia- going round in circles without addressing the root cause of problems.

3) ONE OF YOUR PREVIOUS PROJECTS REFERS TO THE ROSE HOUSE, ONE OF THE MOST ICONIC LANDMARKS OF BEIRUT, FORMER RESIDENCE OF ONE OF THE MOST PROMINENT BEIRUT FAMILIES. IN WHAT WAY WERE YOU ATTRACTED TO THIS HOUSE BY THE SEA AND DECIDED TO MAKE IT YOUR STUDIO FOR SEVERAL MONTHS?

The Rose House is a magical place. It’s more than a building. It’s a living spirit. I had always been fascinated by it since I first saw it during my first trip to Lebanon in Spring 2006. The way it overlooks the sea, faces the setting sun and evokes a timeless era. After transforming another deserted mansion ‘Villa Paradiso’ in Gemmayzeh, Beirut in 2013, I finally felt motivated to go and knock on the door. I had always thought it must be abandoned, but after my wife Noor and I noticed washing on the line on one of the balconies, we realised that there must be someone living there; and so there was, Sheikha Fayza el Khazen- a very cultured lady, whose family had lived there for 50 years. She invited me in to see the house and paint. It was a wonderful experience to be part of her household. I was surrounded by her antiques, fine furniture and the paintings of her late brother Sami El Khazen- who died in Paris in 1988. It was also a sad experience because she told me how she had to leave because there was a new owner. I witnessed the passing of an era, a kind of class and culture which may not happen again. So the work became about capturing this transience and also the modernity which threatens the soul of old Beirut.

It also became a work of social and architectural preservation – I convinced the new owner to let me do an exhibition, organise concerts, theatre performances and several art classes for children and students in the house after Fayza left. It was a great success. People finally got to see inside this magical place that they had always dreamed about but never been inside. This is an issue of creating public space, and giving everyone access to beautiful places – which can function as cultural centres. This is particularly valuable in a country which is divided by sectarianism. These magical places can offer something that a church or mosque cannot- places where we can all come together and share something beautiful- no matter what background we are from.

Unfortunately, since my exhibition ended two years ago, the building has remained locked and empty. It is gradually deteriorating as the owner leaves it to become vandalised and ruined by the elements. For whatever reason, it has not been renovated as promised. We are all praying that the renovation starts soon.

4) NOSTALGIA SEEMS TO BE A RECURRENT TOPIC IN YOUR WORK. LEBANON IS A LAND FULL OF HISTORY, THAT HAS SEEN FRUITFUL MOMENTS OF COHABITATION OF DIFFERENT FAITHS IN ONE SPACE AND TIMES OF DESTRUCTION. CAN ART HAVE A ROLE IN HEALING THE WOUNDS?

Yes. The creative arts offer us a way to process our feelings. I work with many different Lebanese orphanage institutions and with refugees- both Palestinian and Syrian. The children have such talent, and often because they have experienced trauma they have an extra sense of perception and sensitivity. It’s about giving people the opportunity and encouragement to express themselves. The Rose House is a wonderful place for children’s imaginations, and so to is ‘Al Zaher’- another stunning old mansion where I recently did an exhibition with children from Dar Al Aytam.

For the older generation who experienced the Civil War, art can have a therapeutic effect, enabling people to regain some of the beauty that was lost during the war and seeing art or listening to music which enables people to process some of the pain and loss.

5) IT SEEMS THAT YOU ARE EQUALLY INTERESTED IN WIDE VISTAS AS IN THE INTIMACY OF DETAIL. YOUR GAZE CAPTURES THE DIVERSITY OF BEIRUT, A CITY THAT LIVES AT A FAST PACE, NEVER STOPPING – BOATS AND YACHTS AT THE PORT, ROADS JAMMED WITH HEAVY TRAFFIC, BUILDINGS AND CRANES JOSTLING FOR SUPERIORITY… IN OTHER PICTURES ARE OLD LANTERNS AND GARDENS INVISIBLE TO THE NAKED EYE, AROUND A FOUNTAIN IN WHICH THE LEAVES FALL FROM THE TREES…

Yes, I like to look at tiny details and wide views. A flower growing from a bullet hole can tell you about a whole city. From a distance, the crude brutality of Beirut’s concrete jungle is astonishing, yet hidden in its little streets are secret treasures. Like the different visions of Venice described by Marco Polo to the Agha Khan in Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities, Beirut has many faces, all of which are somehow true. In the city, there’s no fiction stranger than truth. It is always a contradiction of opposites.

6) CAN PAINTING AS A “CLASSIC” ART SURVIVE IN THE TODAY CONTEXT OF MULTI-MEDIA AND CONCEPTUAL ART?

Yes. As digital technology becomes more present in almost every area of our lives, we need something handmade, something which has been made with love and care, something with texture and emotion. Painting will always have these unique qualities which cannot be reproduced by a machine or on a digital screen. However, I think digital technology can be very useful for spreading awareness through social media and as a tool to visualise possible outcomes for a painting. I use it as part of the process.

I had an interesting experience when sketching portraits in the Sabra Refugee camp. I was sketching with children and young mothers there who were actually queuing up to have their portraits drawn! It was a lovely atmosphere. Then they saw a photographer and they ran away- afraid of how these photographs may be used in the media. They hid until the photographer left. Then they returned to continue the portrait sketching session. The process of sketching involves a lovely human interaction which crosses cultural boundaries, and is difficult to reproduce using technology. I experienced a similar thing painting with tribes in Ethiopia. It was lovely way to connect and share without the potential exploitation of photography. But sure, multi media and conceptual art have their place too.

7) APART FROM PAINTING, YOU ARE ALSO A MUSICIAN PLAYING JAZZ ON THE TROMBONE AND A LISTENER WHO WEAVES MUSIC INTO IMAGES. WHAT MUSIC ARE YOU LISTENING TO WHILE YOU PAINT?

Music is like fuel when painting. It depends on what mood I’m in and want to create.. Sometimes I’ll paint a picture just so I can listen to a new album! I listen to all sorts of stuff-from jazz by Art Blakey and Miles Davis, blues and songs by Tom Waits, classical by Rimsky Korsokov and Chopin, Arabic jazz by Zafer Youssef and Anouar Bahem, moody electronica like Underworld, Nils Frahm, Olafur Arnalds and Jon Hopkins and trip hop by Massive Attack and DJ Shadow, sometimes 70’s Funk and more recent hip hop. It’s real mix.

8) CAN YOU TELL US SOMETHING ABOUT YOUR CURRENT PROJECTS?

I have a few current projects: one of them is a continuation of my recent project at ‘Al Zaher’, a beautiful old mansion in Beirut which used to be the British Ambassador’s Residence before becoming the administrative headquarters for Dar Al Aytam Social Welfare Institution. I discovered the remarkable history of the house-which is where the maverick British General Sir Edward Spears lived when he collaborated with Lebanese politicians of the 1940’s to remove the French as the ruling power. It was a time when the British and French competed for power in the region. Spears played a vital role in Lebanon gaining Independence in 1943. He was promptly sacked by the British because his empathy for the rights of a small country was seen as dangerous to the concept of Empire. For the exhibition, I painted forty portraits exploring this story and subsequent politicians and other visitors who had passed through the house over the years, but these were removed by the Institution just before the opening of the exhibition for fear of political controversy.

It was an upsetting experience, and a symptom of Lebanon’s fragility and disputed past-even the formation of the country cannot be explored without fear to this day. So I’d like to find another appropriate venue to exhibit the work in later this year, and hopefully get Spears’s fascinating first hand account of the time, along with a great biography by historian Max Egremont translated into Arabic so that they can be studied in Lebanese schools in the future. As long as these texts are balanced with other accounts which may tell another story, then I believe this can contribute to the country moving forward with more confidence and a sense of identity. I’m also making a documentary film about the subject-interviewing certain experts and witnesses.

Otherwise I’m painting more cityscapes of contemporary Beirut from North, East, West and South: NEWS. I’m using a more minimal, graphic approach. It’s a take on seeing the same thing from different perspectives, and an expression beyond the past. What is the city now? I hope to do an exhibition about this.

I’m also always on the look out for another fascinating building to work in. There is an infamous former hotel called the ‘Holiday Inn’- which became the centre of Lebanon’s Civil War. It has remained empty and shut ever since- a haunting testament to unresolved conflict. I have managed to gain access to paint inside, and would love to get permission to do a public event there.

9) YOU TOLD ME ABOUT YOUR TRIPS TO EX YUGOSLAVIA, BEFORE THE WAR. WHAT MEMORIES DO YOU HAVE OF OUR LAND AND PEOPLE?

Visiting the former Yugoslavia in 1990 made an unforgettable impression on me. It was the first time I had traveled without parental supervision, and the first time I had heard young people discussing politics and religion in public. I was fascinated by the mix of cultures, the sight of churches and mosques so close to each other. I made friends with a young man who didn’t want to be conscripted into the army in Ulcinj, now in Montenegro. I heard his stories. I stayed in beautiful Dubrovnik. I saw anti-Communist graffiti and stood in the footsteps of Gavrilo Princip in Sarajevo. I walked across the original old bridge in Mostar before it was blown up. Of course I was witnessing the beginnings of unrest. When I saw what happened afterwards on TV, I felt an empathy for those suffering. It was the first time I had any personal connection to a war. I would love to return and perhaps explore some of the transformative qualities of art that I pursuing in Lebanon.

10) SAY HELLO TO BEIRUT FROM ME AND I HOPE TO SEE YOU AGAIN SOON, INSHALLAH, AS THE LEBANESE SAY.

Haha, I will do. Inshallah, see you again in Beirut, or Sarajevo.