WORDS: ANIMA MUNDI

PHOTOS: FROM PRIVATE ARCHIVE

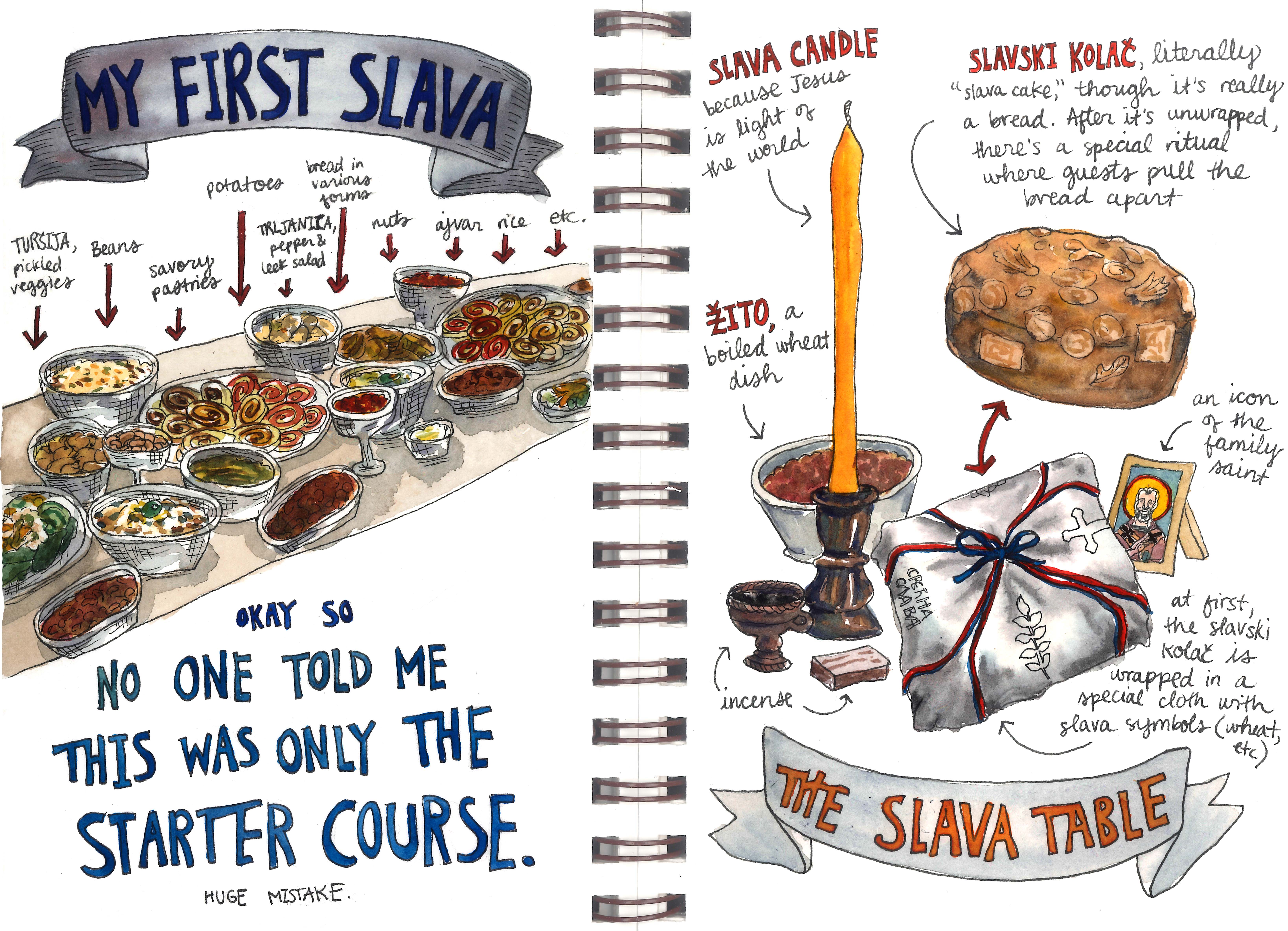

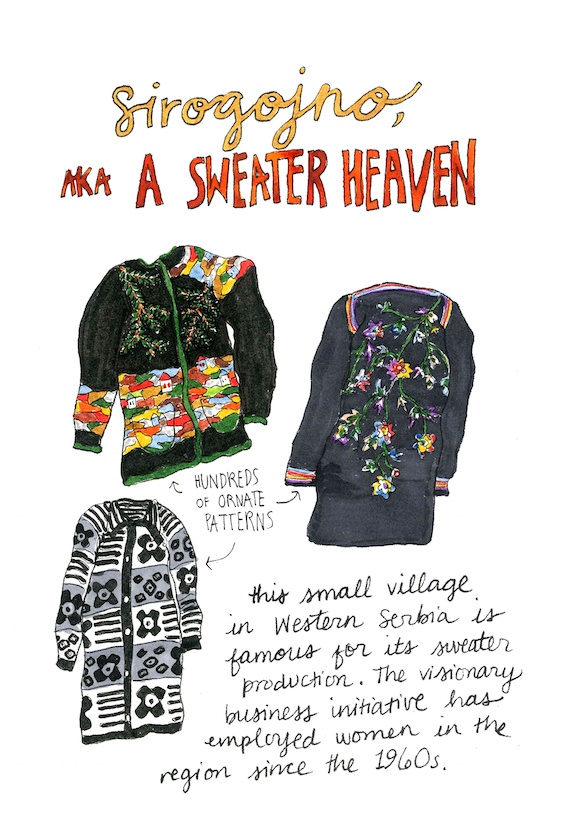

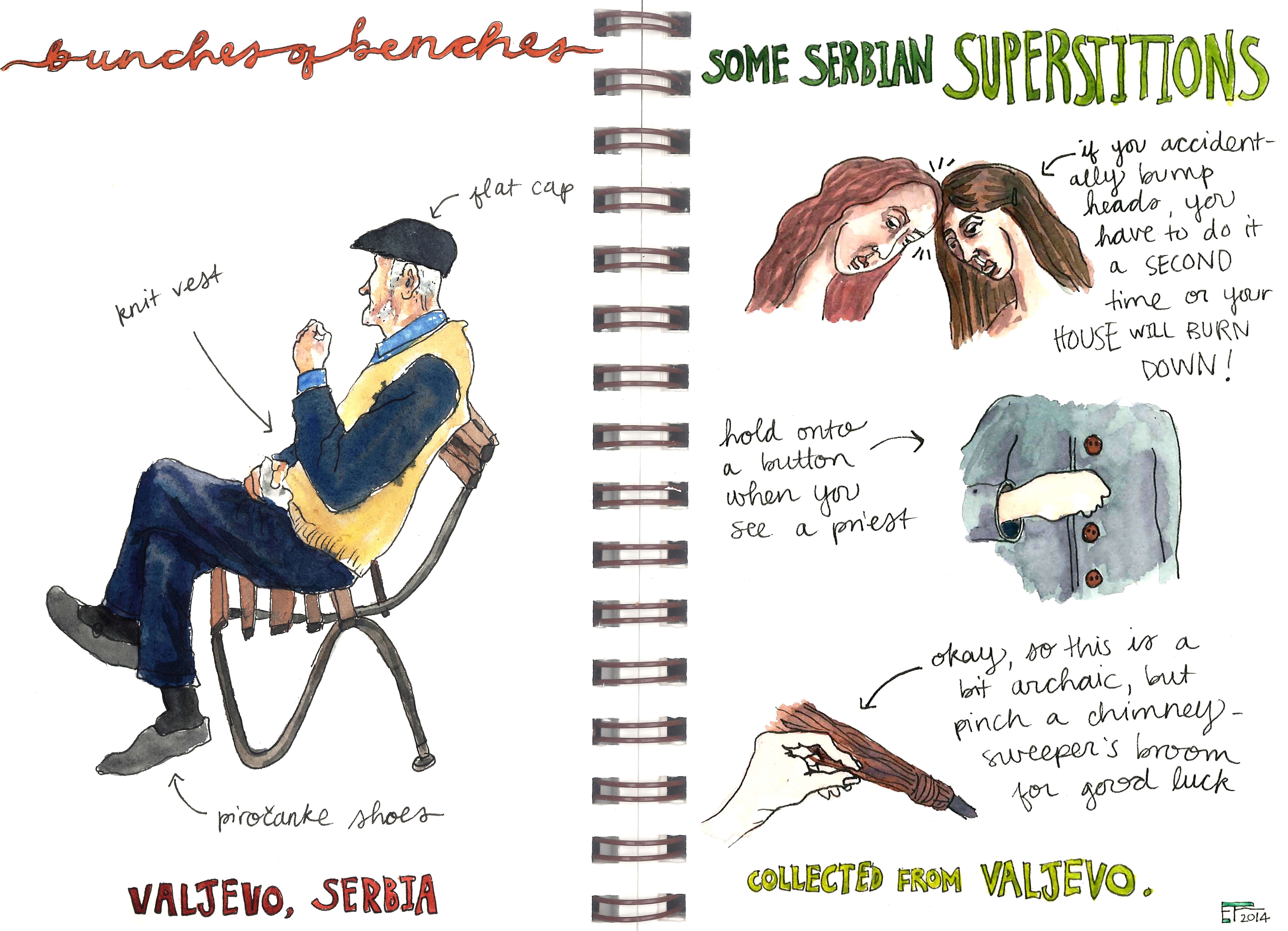

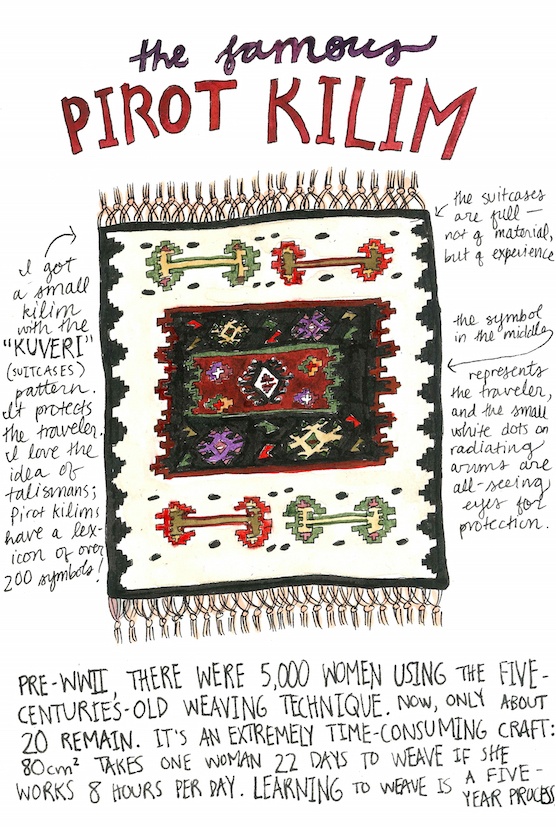

Emma Fick was born in Louisiana, she graduated in the English Literature and The History of Art. In Serbia, she arrived as the Fulbright scholar to teach English in 2013 but she started illustrating Serbia in her own way. She was travelling across Serbia a lot and found interesting motives and details. She reminded us of our identity. Emma´s fascinating story, Snippets of Serbia, presents an impressive illustrated book by the same name. With contours, colors, a few lines of text, she presents us the way we are, our traditions, daily life etc.

Her family history is connected to Serbia. During World War II, her grandmother’s aunt was married to a Serb who managed to get her family of Jewish descent out of Vienna, where they lived, to Belgrade, and then paid for their trip to America, saving them from what was happening in the Europe.

Snippets of Serbia actually represents an extraordinary guide to this country, its people, culture and traditions – here you can find fine details about Vranje, the public transport portraits, Knjaževac, Niš, Stara Moravica, kačamak, krajputaši, lunch on the Tara mountain, obućar, baba Desanka, baba Jovanka, my favorite – baba Bosiljka, and much more.

With the great support and the project of the US Embassy, Fick spent four months exploring Serbia. She visited eight cities where the American Corner has its libraries (Subotica, Novi Sad, Kragujevac, Novi Sad, Belgrade, Vranje, Niš and Bujanovac). She ran workshops in the field of illustration on the topic of visual impressions of the US culture and Serbia.

She has had two illustration exhibitions and she has published a book. Snippets of Serbia is an illustrated journey by Emma Fick.

What is your personal Serbian truth?

My personal Serbian truth is constantly developing and morphing. Like any truth, it’s never complete, and I’m always adjusting it as I get more information and hear more stories and see more places.

Right now, my Serbian truth is the remarkable combination of generosity and scarcity. On the one hand, Serbian culture fosters generosity beyond anything I’ve seen. People share their homes, stories, food, drink, resources, and time. On the other hand, there’s a great scarcity to Serbia: the economy creates an atmosphere of desperation and fatigue, because people are grappling with short resources on a daily basis. Most of the time at the beginning—especially for me as a foreigner—this desperation and fatigue was hidden, swept behind feasts and hospitality. But slowly, as I stayed here longer, it started becoming more and more apparent. The hospitality and daily joys are still there (Serbs know how to enjoy life!), but it exists in tandem with these other, darker realities. (Luckily, Serbs are also equipped with a dark humor that helps them through).

My other Serbian truth is related to the 90s wars. The 20th century was not kind to Eastern Europe, and there’s a lot of residual pain and anger and guilt associated with those wars. Again, I feel like most Serbs harbor two seemingly incompatible feelings: indignant, on the one hand, for lives lost and the crimes Milosevic committed, and suppressed guilt, on the other hand, for what happened in their name. Serbs are temperamental, strong and sensitive, and that makes them very difficult to understand! My Serbian truth right now shows people who don’t want to apologize because, to do so, would be admitting guilt for the actions of a man they themselves were fighting. I think Serbs want to be recognized as innocent before they apologize for what happened in their name, but that’s not possible—it has to go the other way around (if history is any indication). Serbs also feel like they weren’t recognized for the terrible things that happened to them during the war, because history tends to paint “good guys” and “bad guys” with broad strokes. All this makes for a very complicated truth.

My other Serbian truth is related to the 90s wars. The 20th century was not kind to Eastern Europe, and there’s a lot of residual pain and anger and guilt associated with those wars. Again, I feel like most Serbs harbor two seemingly incompatible feelings: indignant, on the one hand, for lives lost and the crimes Milosevic committed, and suppressed guilt, on the other hand, for what happened in their name. Serbs are temperamental, strong and sensitive, and that makes them very difficult to understand! My Serbian truth right now shows people who don’t want to apologize because, to do so, would be admitting guilt for the actions of a man they themselves were fighting. I think Serbs want to be recognized as innocent before they apologize for what happened in their name, but that’s not possible—it has to go the other way around (if history is any indication). Serbs also feel like they weren’t recognized for the terrible things that happened to them during the war, because history tends to paint “good guys” and “bad guys” with broad strokes. All this makes for a very complicated truth.

What did you notice as the most striking, interesting, amazing, strange or funny in everyday Serbian life?

What did you notice as the most striking, interesting, amazing, strange or funny in everyday Serbian life?

Most things I react to you can see in the illustrations. I can’t explain what or why certain things are funny; they just are. I’m most drawn to extremes, of course, the extremely traditional grandmother with headscarf and wool socks, or the extremely stereotypical young woman with sky-high heels and lots of sparkly clothing. I also like details that represent some larger phenomenon: for example, I’ve done illustrations about the cigarette burns in all the ‘kafana’ tablecloths and the signs that proudly proclaim “smoking allowed” instead of “no smoking,” both to speak to the prevalence of smoking in Serbian culture.

How do you notice details for drawing snippets?

How do you notice details for drawing snippets?

Observation is a way of life. I’ve noticed details my whole life; it’s just that now I have something to do with those observations. Before I was putting them into illustrations, they just flew from my mind after a while and disappeared. But now they have a home and a way to become more permanent.

What are the snippets for you in the artistic way and in your life?

It depends. When I was in the middle of the project, they were my life. They were my way of expression. I was working 7-8 hours a day on them. Now, I’m taking a break from Snippets in that particular form, and doing more observational illustrations (with less didactic, explanatory text) in a smaller format. But, like everything, it’s cyclical—once I have enough time off from the Snippets, I’ll be excited to get back to drawing them, which I’ll do in October this year in New Orleans.

What is the personal identity of the nations where you spent some time and showed us the main characteristics of? (Serbia, Bosnia, Macedonia, Montenegro, Croatia, Budapest, Vienna, Krakow, Turkey)

This question is much too loaded and complex to answer in a few sentences! If I could answer it, even. I don’t think my understanding is complete enough to summarize the main characteristics of so many nations.

How do you recognize your own identity living at so many different places?

Well, I have only lived for an extended period of time in Serbia. The other places I was just traveling through, so my understanding of their cultures is much more surface-level. My identity is the same everywhere I go, though. It’s like that quote, “no matter where you go, there you are.” I always feel like an observer, someone slightly on the outside peering in. I felt like this my whole life, though. Even living at “home” in Louisiana, I never felt so much part of the culture as a separate observer of it. My identity is always primarily artist-observer, secondarily participant.